Dear Papa,

It’s weird to be a 52-year-old daughter of a 33-year-old father. Am I expected to love you as a child or look up to you as an elder?

By now, all your children are decades older than you. I, your oldest, have 64.3% more life expertise than you. If we were to meet today, would you melt in adoration with how smart I turned out? Or would you bristle, like (most) millennials, at my process-focussed, work-from-office, uber-disciplined Gen X ways?

As your elder, I sometimes scold you in my head. Why did you climb into the cab from the wrong side of the road that day? You knew how rash the bus drivers were in our part of town.

But let's not go there because it is February. Every year, in February, I become your 11-year-old child and hug the last sight of you tight in my eyes.

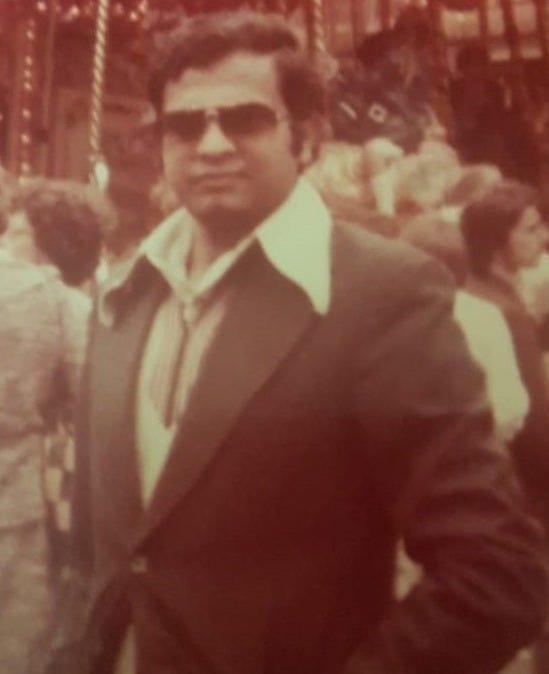

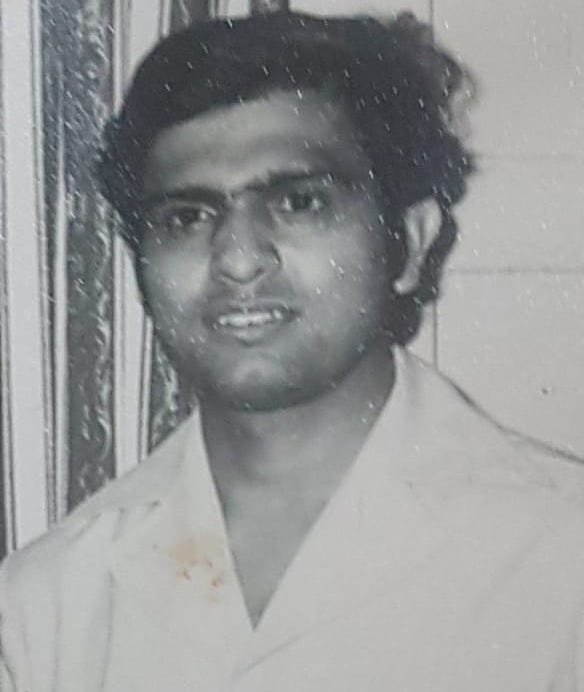

My last sight of you is a ten-second visual, clear and untouched by the haze and press of time. I could have shot it with a 1000-megapixel sensor. The iron gates. The taxi. You. Your half-smile as you held yourself in the seat behind the driver.

I did not allow my gaze to wander away from your face – the only part of you that remained untouched. Your white shirt and blue jacket would be returned to us later in a wrapped polythene pack.

You died on a crisp February day. It was late afternoon when the adults had slipped under the covers of a siesta, and I was loitering in our driveway.

Our driveway had hosted a big birthday party the evening before, but the long rectangular passage had already been swept clean. The tentwallahs had rolled up the bales of coloured shamiana cloth and heaped them in a corner. Baby pink and sunshine yellow —the shades of my little cousin turning one.

Jagdish and his small gang of cleaners had stuffed the party litter into gunny bags and propped them in a corner. Limp balloons, torn festoons, toffee covers, broken whistles, and a Khoi bag in shreds: the afterward of joy sat patiently in bulky brown bags, waiting for their disposal.

By 3 p.m., the driveway had been bathed in buckets of water. The lines of the badminton court were back in sight. I was walking, head down, on the straight white borders of the court, step by step, one foot before the other, as if the white line were rail tracks in a field full of kaash flowers.

Then, a cab honked outside. Bahadur jogged up to the iron gates and pushed them open. I followed. I saw a cab driver pacing on the road, failing his arms, calling out to us. The two rear doors of the vehicle were wide open.

My eyes fell on you. The hurt soldier in the cab.

Bahadur broke into a guttural scream. “Babu, babu, kya hogaya!”

You gestured for me to go away, to not come close. Or were you asking me to run back in, and fetch the elders, quick?

I fled in the opposite direction, towards the house. Everything after that is a haze.

Papa, the tentwallahs returned after a week to cover the driveway with bales of white cloth and flowers of a hundred shades of ivory. The Ashoka trees could have added a nice green border to the white drapes. But they were planted a few months after your death to mark Chacha’s wedding.

Eleven months after your death, the family organized an elegant wedding. The driveway underwent a makeover. Its ordinary grey cement floor was yanked out and replaced by marble tiles—large grey slabs with black and white flecks.

The grounds on which we played, rode cycles, parked cars, and held get-togethers had turned posh—a statement that we were moving on from loss and moving up in status.

‘Babboo would have wanted it this way,’ the elders of the family said.

As your elder, I know that the dead are often misused to justify the wishes of the living. But it's February. So, I will stay as your 11-year-old child and ask you a few questions.

Did you approve the removal of the cemented flower beds that lined the entire driveway? We posed in front of them for all family photographs. I watered its black Bengal soil and picked the blooms of genda, sadabahar, rose, bela, and jaba for the Pooja thali on weekends.

I sobbed when the flowerbeds were destroyed.

Daadi must have raged at the uprooting and demanded compensation. So one day, the labourers cut neat squares on either side of the driveway and planted 12 Ashoka trees with geometric precision in the hollows.

Now, the driveway looked like a giant chessboard with green guards on either side. The marble was too expensive for us to mark it with the white lines of a badminton court.

Soon, the tentwallahs returned to dress the driveway like a bride: crimson, marigold, and Fuschia—the colors of an arranged marriage alliance. Golden lights shimmered along the shamiana like delicate jewellery. Chairs dressed in shiny white covers sat along the Ashoka trees.

The driveway hosted many wedding events—tilak, sangeet, haldi, baraat, pre-wedding and post-wedding dinners, a grand meal for everyone who worked in our shops, and impromptu side parties for gangs of uncles, aunts, elders, and cousins who converged on our home from all parts of North India. Jagdish and his cleaners showed up every morning to sweep away the party litter and hydrate the exhausted driveway with hosepipes.

Papa, in that 12-month cycle between a birthday, a death, and a wedding, the driveway had echoed with the squeals of toddlers, the animal howls of Dadaji as he lifted you on his shoulder, the cheers and jeers of kids in relay races who had quickly forgotten their grief, hushed neighbourhood conversations on the politics of the day, and the dholkis and shehnai of an alliance—in that order.

Because 1984 was no ordinary year. Grief and shock visited us in an unstoppable flow through its 12 months. Between sobbing, dressing up, and witnessing makeovers, we were jolted by news of the storming of the Golden Temple, of horrific terror in Punjab, an assassination, blazing riots, the burning of a far-away city where friends and relatives lived, and deep grief as a poison gas entered the lives and lungs of millions in a city.

At night, when I huddled next to Mummy, she would tell me that she saw herself in the images of the other young widows on the TV screens. She wrote prayers for us and their children in a little diary and placed them at the feet of the Gods on her dressing table, which she had turned into a pooja alcove. I wrote a few prayers, too.

Dear Papa, let me now write to you as your elder because your child has told her story.

As your 52-year-old, I think our driveway was trying to send us a message in 1984. It was telling us that life holds grief between bookends of celebration. Why else would it have hosted a grand birthday party a day before your passing and then dressed up for a wedding a month after the mass deaths of Bhopal?

Or Papa, was it you trying to tell us that in the years to come, the four of us—your wife and three children—would forge hope, meaning, and life mostly through the ins and outs of grief? Were you giving us the guarantee that even in the worst of years, we would have a steady supply of small and big celebrations?

Papa, your guarantee was your gift as you walked out of the driveway for the last time on 19 February 1984.

On February 19, 2025, we will have lived 41 years without my father. I often wonder about the kind of father he would have been to a difficult daughter like me.

At work, when I design and host intergenerational conversations, I think of how these conversations would twist if I were to have them with my father. Would I speak to him as a Boomer or a millennial?

How does a 52-year-old daughter talk to her 33-year-old father? This essay is a response to this question that has been sitting in my head for some time now.

I have no words to convey what I am feeling right now Manisha. This essay was heartbreaking and soothing at the same time. I cried through it and smiled at the memories. You've given us all a precious window into your world and, in some ways, my world, too, even though I was so much younger. Today, the faded memories of childhood have resurfaced like a tornado. You are a master storyteller, but this essay is not a study in craft. It is something else - a gentle ode to your father, who would undoubtedly be immensely proud of you. Lots of love.

This was a gut-wrenching, soul-expanding portrayal of a life lost too soon. Lots of love and healing to you...